Haigh Hall

School Lane, Haigh

Description

2023 - Currently undergoing £20 million restoration as part of the Government Levelling-Up Fund .

History of the Hall.

James, who became 24th Earl of Crawford in 1825 and was created Baron Wigan of Haigh Hall, was the builder of the present building. The old hall, a relic of Norman times, had been considerably enlarged in Elizabethan times, had been allowed to fall into a state of dilapidation after the death of the last Sir Roger, and had been reinforced by Earl Alexander.

Earl James, who had inherited the engineering and practical abilities of the Bradshaighs as well as the business ability of his father, undertook the task of rebuilding.

The work was started about 1830 and completed about 1849. It was built on the site of the old hall, and the Earl lived in Park Cottages, then comparatively modern, while the work was being carried out, and, as jt was the age of nicknames, earned himself the nickname of Jimmy in the Trees. He drew his own plans, directed the workmen himself, and used his own materials.

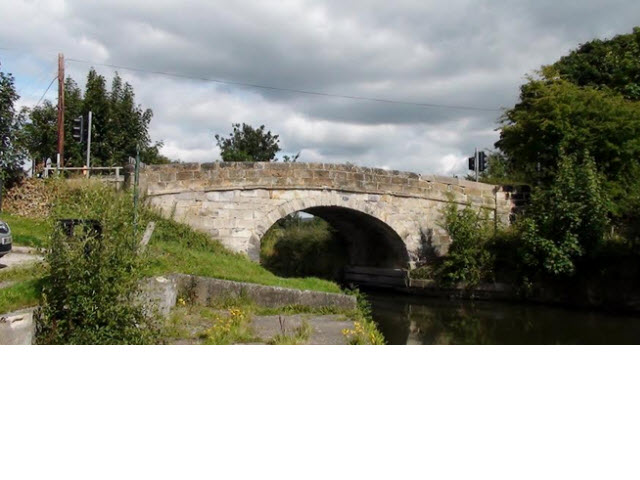

It is an imposing and solid square block, typical of the period, built round a small courtyard. The stone of which it is built is a hard sandstone, which was quarried in the Parbold area, brought to Haigh by canal, and dressed on the spot by John Haig, a Scots apprentice, with steam-driven saws specially designed for the purpose. The supply of building stone of that quality ran out, so the top part of the Hall was not completed in the way originally intended. The walls now have a slight tendency to lean outward owing to mining carried out all round, although not actually underneath the Hall, which stands on a plateau, and is quite safe. The iron work used came from the Haigh Foundry.

Some of the doors attract one’s attention. They arc of fumed oak from the estate, a lost craft today on account of the time taken to complete the process, while the doorways and surrounds are made of wood brought from the Earl’s Jamaican plantations. The marble fireplaces and plaster ceilings arc worthy of notice and were brought from Paris, the only materials which did not come from his own estates.

Certain ideas and materials were incorporated from the old hall. A narrow twisting staircase guards one approach to the Earl’s bedroom, perpetuating the idea of a knight being in a good position to defend himself and his lady. In the reign of Queen Anne, Tim Runnigar, a Wigan woodcarver, supplied a staircase, gallery, and three-arched arcade for the sum of £50, half of which was paid on delivery of the materials, and his work is of high quality. The staircase was used in one part of the present building, while the arcade is in one of the present refreshment rooms.

The house is full of the Earl’s inventions. The windows fit into draughtproof steel slots, easily opened from inside, but impossible to open from outside. The outside doors had no locks and could not be opened from outside, something that had to be rectified in the last war in the interests of civil defence.

Inside doors are fitted with patent hinges allowing them to swing back through a complete half circle, and by a twist of the handle automatically bolt themselves open. The staircases are keyed, the bottom stair holding the weight, but to an observer they appear most unsafe.

The main staircase was strengthened by the addition of steel girders in 1951, as the Earl’s staircase was made to stand the ordinary weight of a private residence, and not that of a public building. The roof is made of lead, which being so heavy would collapse were it not fitted with springs underneath it.

All doors leading to the back staircase, which runs from the top of the house to the kitchen quarters, were fitted with green baize. All the corridors look alike, particularly when furnished and carpeted, so that when a workman was called in to do a he was told to look for a green baize door when he had finished. Heating was by means of a hot air system combined with open fires. The system was most effective for keeping the corridors and large rooms at an even temperature, but seven boilers were needed and used a lot of fuel. The open fires gave additional warmth and cheer when sitting in the drawing-room, or having a meal. The last parts to be built were an extension on the roof, called the Noah’s Ark, where the Earl’s sons slept, and the portico, the large flagstones being specially noticeable.

The material for these last portions came from the delph near the Alms-houses in Leyland Mill Lane.

Reproduced from a booklet produced in 1957 by H.H.G Arthur, Wigan Council Librarian

Haigh Hall History

A collection of articles and resources relating to the history of the Hall, the people, and the wider estate of Haigh.